Can a Transformer “Learn” Economic Relationships?

Revisiting the Lucas Critique in the age of Transformers.

Written with Arpit Gupta, subscribe to his blog here.

In the 1960s and 70s, the standard way to do economic analysis was to feed data into a model and then estimate the relevant parameters. For example, based on historical data, economists believed there was a stable tradeoff between unemployment and inflation, i.e., the Phillips curve. Policymakers believed they could exploit the tradeoff by accepting higher inflation in exchange for lower unemployment. However, when oil price shocks in the 1970s generated both inflation as well as rising unemployment, expansionary monetary policy failed to deliver the predicted results. Instead of lower unemployment, the economy experienced “stagflation” of higher inflation combined with high unemployment, suggesting that the historical relationship had broken down.

So what happened? Expectations of inflation made workers and firms change their behavior: knowing that inflation was going to be higher in the future, workers demanded higher wages and firms hired fewer workers today. It turns out that a statistical correlation between lower unemployment and higher inflation is not exploitable by policymakers as an intervention, because their policy action induced a different set of behavior by agents.

Enter Robert Lucas with his famous 1976 treatise “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique.” This Lucas Critique, as it came to be known, argued that economists had been interpreting correlational relationships from historical data as structural, meaning they were invariant to policy changes. But they weren’t. The economic agents which generated the data may change their behavior in reaction to changes in policy, which—as the Phillips curve example showed—can shift the observed relationship between variables. The Lucas Critique essentially argued that reduced form methods were only able to estimate the local equilibrium and hence would not be able to predict outcomes to a policy shift.

His suggestion was to use structural models of the economy as these will better predict responses to policy changes. Specifically, if one microfounds the structure of people’s preferences and firms’ objective functions and scales up, then it is possible to predict the impact of policy because the model will take agents’ responses to it into account. This Critique had an explosive impact on economics: the “microfoundation revolution” resulted in a complete shift in how macroeconomics was done. Out were the reduced form regressions, in came the representative agent models.

But the structural approach comes with costs. For one, the predictions will only be as good as the model. If the models were misspecified or the exclusion restrictions were “arbitrary and incredible,” then the predictions were not going to be very good either.

Transformer models and Learning Causal Structure

In this post we revisit the target of the original critique: the model estimates from running fairly simple correlations did not take into account the structure of the economy, and therefore make the wrong predictions when policy shifted. Now consider transformer models. In principle, there is little in the architecture of such models to suggest that they can learn the structure of the data generating process (DGP) from seeing the data. But recent work has shown that transformer models do seem to learn DGPs–-encoding the causal structure during training—and are robust to distributional shifts at least in the case of “nearby” DGPs (e.g., models of the same class). Recent work by Ben Manning, Kehang Zhu, and John Horton shows how transformer models can automatically propose structural causal models and test their implications through in-silico experiments with LLM-based agents.

This emergent property suggests that transformer-based LLMs may, in principle, be able to make predictions for policy shifts in economic settings. How would one test this? One test was suggested by Pontus Rendahl: take a transformer model and train it on economic data simulated by a known structural model. Will the model be able to predict responses to policy shifts?

So that’s what we did. We took the New Keynesian (NK) model and simulated a bunch of data. We then trained a transformer on it, took a hold out policy regime and predicted the response. How well does the transformer model predict the policy response?

Before getting to the results it’s worth clarifying what this experiment is doing, as well as its limits. The question it’s answering is the following: let’s assume that the real model of the economy is NK. The transformer model sees data from this economy and predicts a policy response. Like the econometrician, it has the history until time t and must forecast the state of the economy in period t+1. How well does it do? If it does well, what does this mean? It means that given the underlying model of the actual economy (which may or may not be NK), the transformer will be able to “learn” the DGP at least well enough to make well calibrated predictions. Here is what the experiment cannot answer: 1) will the predictions change if the relationships between variables change, 2) does the model actually encode the DGP in a way that can be elicited (research by Keyon Vafa and others makes us pessimistic on this), 3) are the predictions robust to extreme policy shifts? Beyond these limitations, the obvious one is welfare analysis: the black-box nature of the transformer model prevents the researcher from saying much about welfare given various counterfactuals, which the structural approach allows for by design. But here is one aspect of the exercise that we do not view as a limitation: the NK model has a fairly simple structure—perhaps the transformer model is able to make predictions from data simulated in this framework, but it will do a lot worse if the structure is more complex. While this would certainly be a limitation for the transformer-based approach, the same critique can be applied to the structural approach. Specifically, if the NK model is too simple to generalize from the transformer approach, it is also too simple to model the economy.

Transformers tracks the NK model well

Ok, with these qualifications out of the way (and we’re sure to be missing some), here are three sets of results.

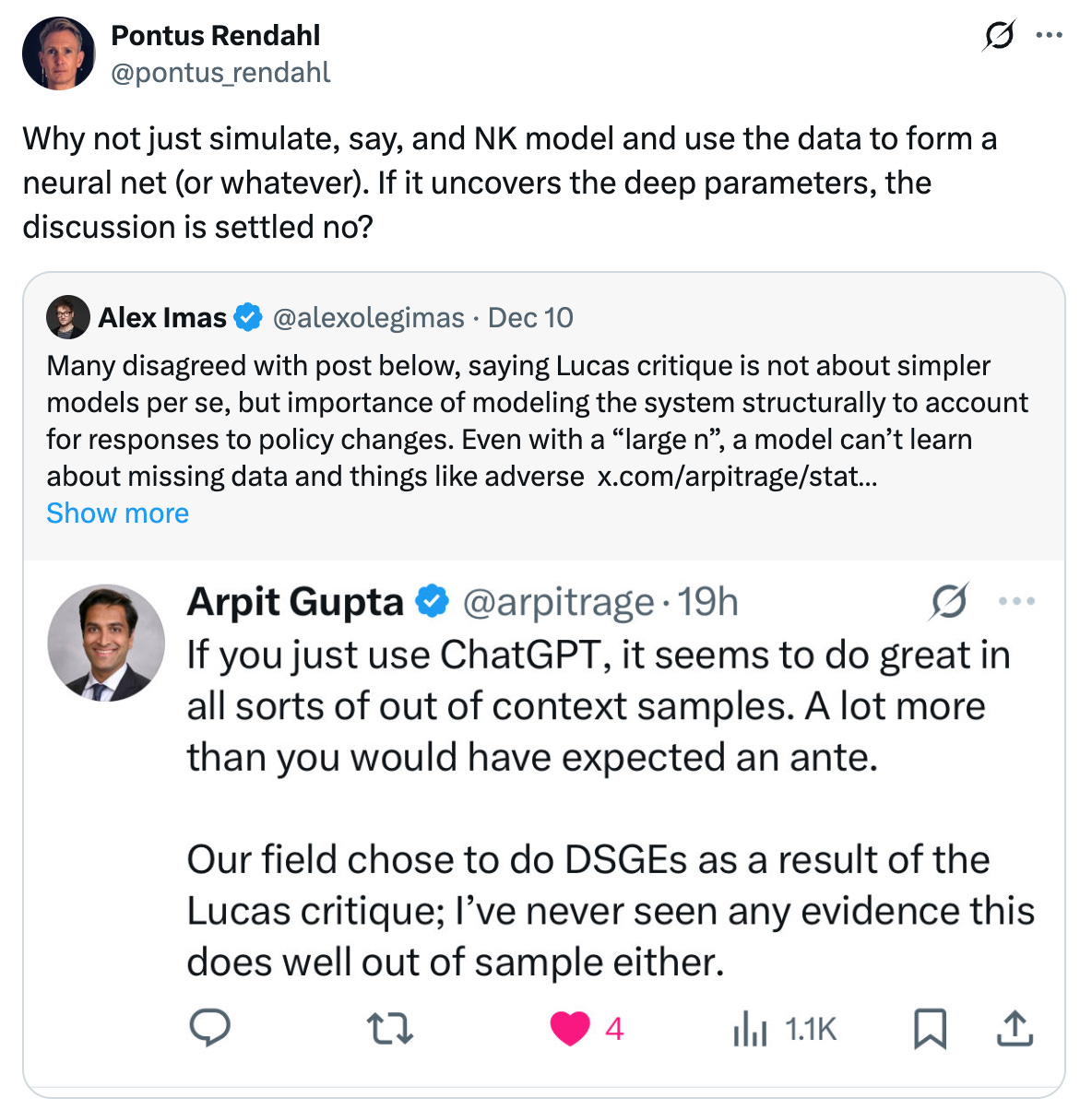

The Transformer tracks the NK model’s realized dynamics across the three key observables: output gap, inflation, and interest rate.

To evaluate model fit, we picked some out-of-sample parameters which the model never saw in training. We then simulate a NK model under these parameters for 50 periods, for which the key three observable variables are the output gap, inflation, and the interest rate. We then give the transformer the parameter vector and innovation, and ask it to forecast the endogenous economic variables, plotting the truth (solid line) against the transformer (dotted line).

The transformer is basically on top of the truth, suggesting that it is able to match the dynamics of the real system quite closely. It even manages to get the turning points and large deviations right, and matches the levels quite closely as well. The main deviations are at the extreme peaks and drops, where it slightly underpredicts the magnitude of the shift.

By itself, this evidence doesn’t establish that we can just switch over to transformers instead of solving DSGE-style NK models. The objective is a little more limited: that the transformer model appears to do well in out-of-sample forecasting in a simulated NK world.

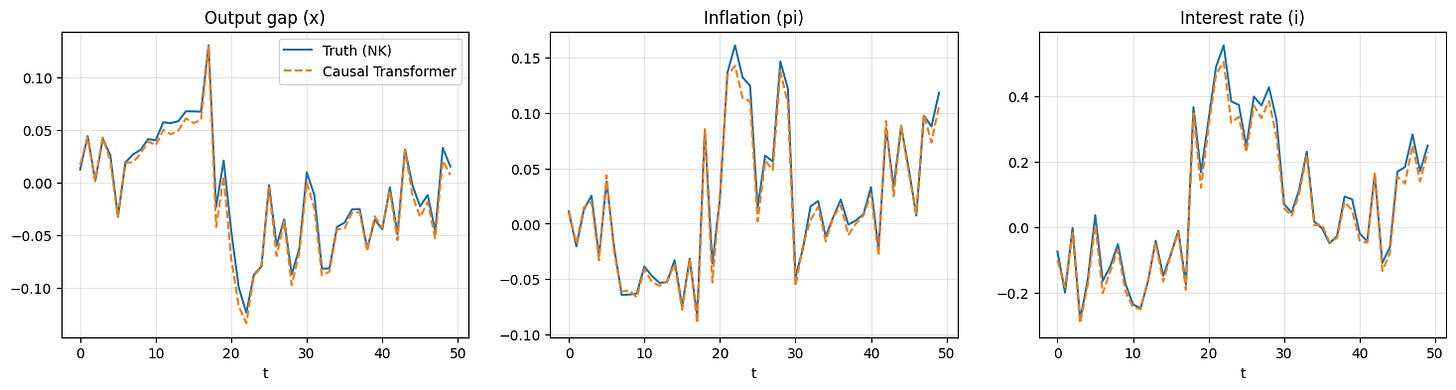

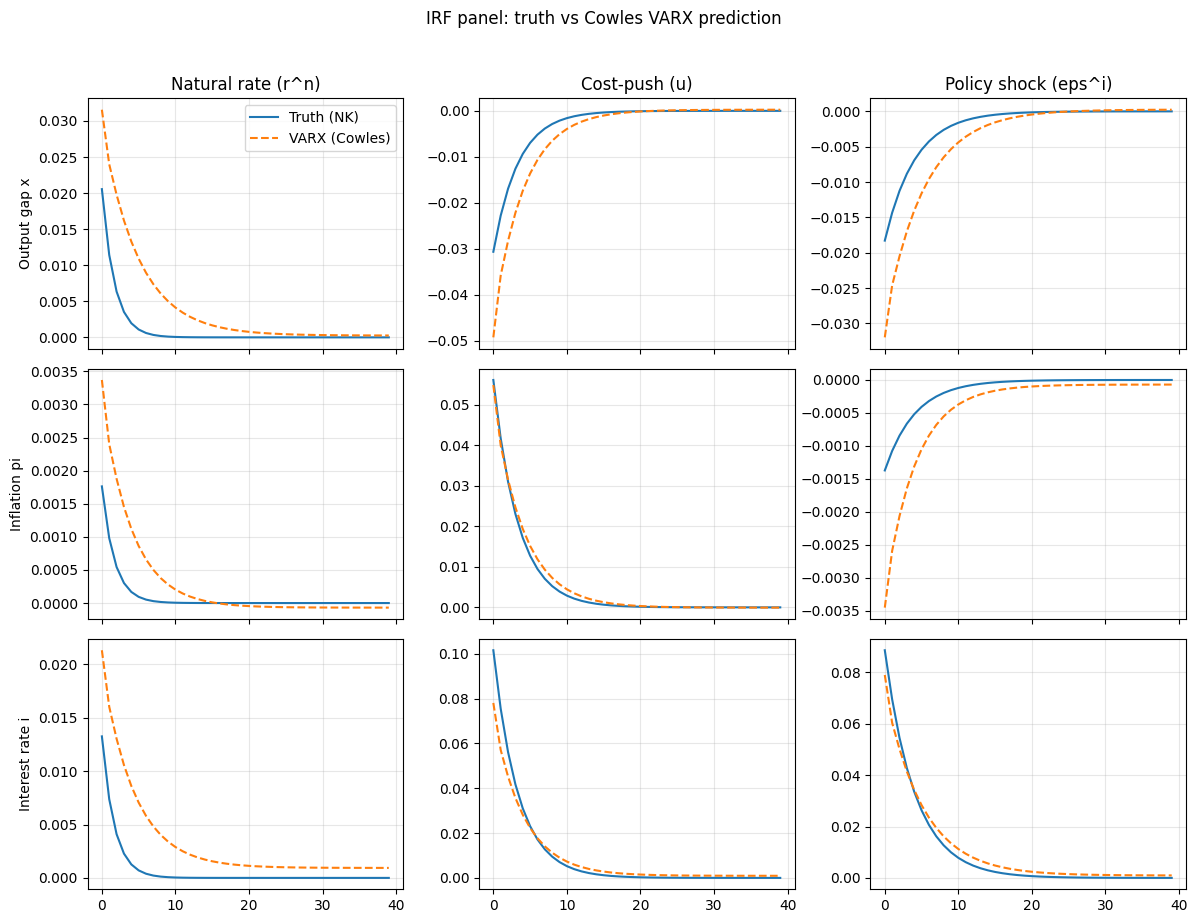

The transformer model has some success in forecasting in response to policy shocks.

This is really the central question for evaluating success at the Lucas critique: how well does a model trained in one set of parameters match the counterfactual economy’s trajectory after being hit by a different set of shocks? That is, how well can a transformer model predict policy counterfactuals from a different regime?

We test this by drawing the holdout parameters, comparing across three types of shocks (natural rate, cost push, and policy), and plot the true impulse response functions (solid line) against the transformer prediction (dotted line). The test is whether the transformer, having been trained in one regime, can accurately trace out the effects of a clean shock out of sample.

We find the transformer generally gets the sign correct in the short-run, and is close in magnitude in the long-run. Ie, if a policy shock raises the output gap and lowers the interest rate, the transformer generally accurately predicts the direction of the effect at onset and gives us a rough magnitude.

One place the transformer model does more poorly is in estimating the dynamics of the impulse-response. The transformer exhibits a bit too much oscillation and overshooting, including sign-shifts.

This suggests that the model has not completely “learned” the true state of the economy in a structural sense, and therefore cannot provide a strictly accurate guide to causal effects.

However, how much do these effects matter in practice?

Theory versus practice

In a famous essay, Milton Friedman argued that the key to evaluating the methodology of an economic theory lies not in the realism of its assumptions, but purely in the predictive power of its conclusions. He drew the analogy to modeling pool players assuming they have access to the accurate mathematical formulas determining billiard ball trajectories. In reality pool players use heuristics and mental shortcuts, but this assumption might nonetheless be accurate in predicting shots by expert pool players, who have converged closer to the prediction of an optimal physical formula.

Of course, the intuitions from the two UChicago economists Lucas and Friedman are at complete odds in terms of practice. If the only thing that matters is prediction, then we can afford to be quite agnostic about the precise data generating process as long as we are happy with the model fit. But if the main thing that matters for causal inference is having the “right” representation of the state of the economy, then the predictions alone are not good enough and we really need to nail down the true economic model.

The results from our experiment suggest that transformers sit somewhere between these two extremes. The fact that a transformer can take a new policy regime and a clean impulse shock and still get the sign at impact and rough magnitude is already a non-trivial achievement that advances beyond simple reduced form correlations. However, the volatile dynamics are a reminder that getting the rough direction correct doesn’t necessarily entail learning the true structure. Whether this matters or not depends a bit on the application.

The Friedman-friendly interpretation, in other words, is that transformers do seem to learn some useful and regime-transferable predictive technologies which enables a limited degree of extrapolation out of context. Despite not having “learned” the true state of the economy, the model has internalized some regularities which allow it to approximate the conclusions we care about.

The Lucas critique does still bind here, however, because the model has not yet learned the true state representation, and hence the true nature of shock propagation in the economy. The shape of the IRFs can be wrong even if the endpoints are correct.

Moving beyond the Lucas Critique

Transformer models represent a huge advance on the purely reduced form models criticized by Lucas.

Another natural benchmark to consider the success of the transformer models is through a direct comparison of the Cowles-style regressions Lucas was criticizing. We take our same simulated NK data and estimate a linear reduced form dynamic system in which the output is predicted using lags of historical variables.

We observe substantially worse model fit, as judged by comparing the true data (solid line) to a reduced form prediction (dotted line). The mean square error is about an order of magnitude higher in this predictive exercise than in our transformer.

When we look at impulse responses, the reduced form model also really struggles to get the magnitude of the impact right, especially at inception. Generally the reduced form model drastically overestimates the true magnitude of the effect.

You can see based on these results where Lucas was coming from: if the economy genuinely did follow an NK structure, you would be pretty far off in estimating true policy counterfactuals through a purely data centered approach. Opting for the structural route was a reasonable way to try to improve policy credibility with the technology available at the time—so long as one was prepared to believe the implied structural model of the economy.

The Lucas critique logic does hold today as much as it did in the 1970s. What has changed is the technology of approximation.

When Lucas made his critique, he was responding to an econometrics which was essentially linear, based on a small number of parameters, and reliant on strong identifying assumptions. The toolkit consisted of lagged variables, VARs, and some simultaneous-equation systems which had a hard time representing the true, non-linear, and forward-looking nature of the economy. It’s easy to see why such models would struggle at getting out-of-sample policy forecasting right.

Transformers, and the new AI machinery around neural nets more broadly, represent a huge advance in this kind of representation. With much deeper context windows, these models can keep track of long and complicated histories and do a much better job at prediction. If the model can infer something close enough to the true hidden state of the economy from observable variables, it can transfer that knowledge to nearby policy regime shift states because the underlying economic logic is the same even as the states change. This is what we see in our forecasting plots and (somewhat imperfectly) in the IRF graphs: the model is learning something like a state-space model, at least enough to forecast, without knowing the true state-space.

So what do we conclude from all of this?

First, that advances in artificial intelligence do weaken the practical impact of the Lucas critique relative to the models criticized at the time. Newer transformer models can learn predictive relationships which remain partially stable across regimes, at least holding fixed the true structural nature of the economy and for some “nearby” policy shifts. This is something already that Cowles-style models struggled to do.

However, simple transformers alone do not abolish the Lucas critique. If the goal is accurate counterfactuals for policy, rough approximations aren’t enough. You probably want greater assurance that the model’s internal representation is close enough to reality so as to be comfortable relying on the model for guidance. Of course, the same challenge applies equally to the DSGE objects in modern macro, which have had mixed success in forecasting and prediction.

All of this suggests a natural research agenda going forward. Structural models have their place in economics, and will retain important advantages in terms of legibility, being able to cleanly trace mechanisms, and evaluate welfare and counterfactuals. But we should be increasingly willing to explore transformer-style models and other tools from ML and AI to explore purely data-driven model generation in our field. As this technology is likely to just get better over time, we should grow more comfortable in thinking of “structure” as something which can be learned, rather than assumed.

Appendix

Addendum

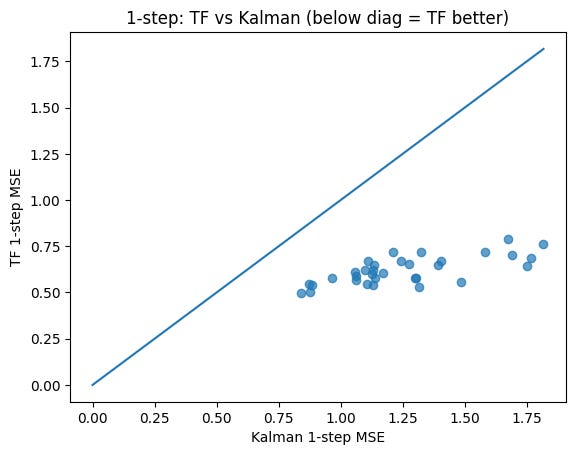

In response to this post, we got some good comments by Olivier Wang and Nathaniel Bechofer, among many others. Our design here was intended to be as simple as possible to illustrate the use of transformers, but there are two potential issues with the comparison. One, the transformer model does have access to the parameter vector and innovations. Note that while this helps the model understand structure, the model does not assume linearity in the underlying DGP, so there is still a non-trivial step mapping the parameters and latest data point to a forecast of the next period. Second, the linearized NK model is already a pretty good fit for the VAR approach, so it is hard to improve on that baseline too much in this case.

To address some of these issues, we created another experiment in which we have a causal transformer as before, but it observes only the y variables, i.e. it has none of the benefits of observing structure. We compare this to a Kalman filter, which is a reduced form model with a similar handicap of not inherently matching up to the precise design of the NK experiment. We then show the MSEs of the two approaches below, which show the transformer (TF) substantially outperforms the Kalman filter.

To be clear, we are not asserting that the (simple) transformer model here is the last word—there are obviously many other implementations of these methods which can do better. Nor will the results necessarily extrapolate to other economic frameworks, or to areas in which the economic regime changes entirely (though we are not so confident our existing DSGE methods work for such drastic changes either!). Our goal here is pretty modest: we are just highlighting the improved predictive power of transformer models relative to the technology available in the 1970s in the specific framework of the NK economy, which has some relevance in thinking about the bite of the Lucas critique in shaping the research we do.

Great essay btw, big fan of applying transformers to other domains. Meanwhile, I skimmed the code. Think your solve_policy_matrix solvest eh wrong linear system, it's NK-like not NK I think. M = np.kron(R.T, A) + np.kron(I3, B) (+ instead of -) . also since R is diagonal you could just solve column by column, would be easier. The pooled varx is also thetea agnostic btw.

Also, thinking out loud, since the transformer is learning input as theta and history of innovations, output as yt, the mapping is linear, I wonder whether we should make it more complex since we know transformers can learn linear-ish relations quite well anyway? The tests also checks that model runs btw, I assume that's intentional.